Jeremy VanDerWal received funding from National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility and receives funding from NCRIS programs including ANDS and RDSI.

April Reside received funding from the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility

ian.atkinson@jcu.edu.au receives funding from the ARC, the Queensland Government and NCRIS programs including ANDS and RDSI.

Stephen Williams receives funding from National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility.

James Cook University apporte un financement en tant que membre adhérent de The Conversation AU.

Voir les partenaires de The Conversation France

We have all heard the calls to translate research into action, and have it influence policy and management. Each year, volumes of research are published that could help policy makers make better decisions.

Yet all-too-often it goes unnoticed. The reality is that different priorities, political agendas, personalities, data licensing, etc. often stand in the way.

In rare situations, the stars align and research rapidly informs policy and management, producing positive outcomes in on-the-ground environmental management. This is one such case. In this article we have three different perspectives on how it all came together, and what lessons can learnt from the experience that can be applied to other attempts to have research inform policy.

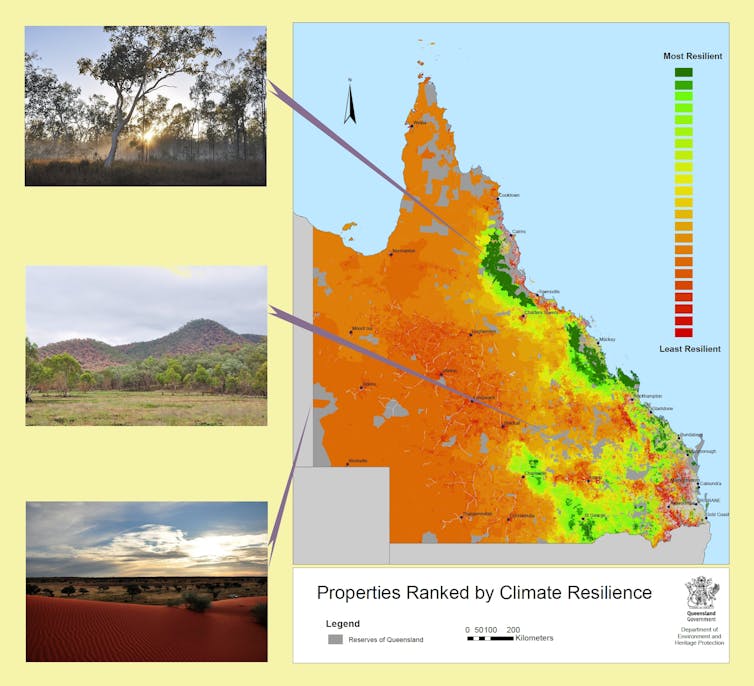

Earlier this month, the Queensland Department of Environment and Heritage Protection (EHP), released a heat map highlighting climate change-resilient areas for vertebrates across Queensland as a part of its Landscape Resilience program.

The heat map was based on research data provided by James Cook University (JCU) researchers at the Centre for Tropical Biodiversity and Climate Change. Within weeks of receiving the data, this prioritisation was, and still is, informing additions to Queensland’s protected area network, enhancing the resilience of Queensland’s unique wildlife for the future.

This is a terrific example of how research can genuinely benefit the public through its influence on policy. We thought it would be useful to reveal how this came about from the perspectives of the JCU researchers, the EHP staff and the eResearch staff facilitating the knowledge transfer, and highlight some lessons learnt that could help such endeavours be repeated.

– Jeremy VanDerWal, Stephen Williams and April Reside, James Cook University

“Publish or perish” is what we are trained on, and engaging with end-users is costly – in terms of time, differences in research priorities, provision of data in suitable formats and it is not recognised on our resumes. This is in spite of wanting our research to have an applied impact.

In this case, a long history of biodiversity research made the Landscape Resilience program possible. A series of Australian Government funded research programs – including the Rainforest CRC, the Marine and Tropical Sciences Research Facility MTSRF and the National Environmental Research Program NERP – within the wet tropics rainforest generated knowledge that was scaled up for an Australia-wide analysis of climate/biodiversity refuges, supported by the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility NCCARF

Hoping to have an applied impact, we have made our research outputs open and usable by publishing data online in different formats, such as via the Climate change and biodiversity in Australia (CLiMAS) and Edgar web portals, with some uptake and usage.

However, here our data were picked up and put into action within weeks of making it available. This was due to the vision and analytic capacity of the EHP staff. EHP combined our data with its own policy/management priorities to inform land acquisition strategies for increasing the resilience of the protected area network. From our perspective it was a fantastic example of how research should inform policy and management.

In 2013, we were fortunate to have a large volume of relevant, usable data provided by JCU. The data resulted from extensive modelling that predicted climate change and how suitable climate for wildlife might change. So began EHP’s Landscape Resilience program, an integrated approach to climate change adaptation for Queensland’s protected areas.

For years prior, key staff from Queensland’s environment department and JCU looked for ways to influence policy makers into recognising the looming threat to biodiversity posed by climate change. Their influence eventually manifested into the aforementioned NCCARF study.

Rather than expecting government to adopt findings that couldn’t account for other constraints placed on its activities, researchers supplied their data freely via university infrastructure and provided support.

A new working partnership was formed that will place Queensland as a world leader in climate change adaption for biodiversity conservation.

Promoting research demands new ways of thinking that can be confronting to researchers. JCU is using its eResearch Centre to remove some of these barriers through a range of services and tools, such as the Tropical Data Hub. With the researchers, we provided access to national computing infrastructure for their research, data portals and collaboration toolsets.

Transferring research data is nothing like downloading a movie. Sharing massive data sets is complex and demanding. All infrastructure must be sufficiently fast and capable of manipulating data on terabyte scales without error.

For the heat map, the data (~2TB) was reformatted for EHP and transferred through a dedicated high-speed connection so that data was available for use within hours rather than weeks.

This was only possible using the services of NCRIS programs such as Research Data Storage Infrastructure (RDSI) for storage, AARNet for the networking, the Australian National Data Service (ANDS) for data management and the eResearch expertise in agencies such as the Queensland Cyber Infrastructure Foundation (QCIF) to make the background complexity vanish.

This let the researchers focus on research and the end-users focus on the content, not the mechanics in the background.

There are number of lessons learnt from this successful connection of research with policy that might be useful for future ventures of a similar kind. To be a success, this example required:

All of this came together here to provide an amazing result: a state-wide protected area system that is more resilient to future climate change than it was just 18 months ago.

This success story has opened the door for a new partnership between these researchers, facilitators and practitioners. In a time when Australian investment in both scientific enquiry and the public sector are constantly challenged, leveraging each other’s strengths may be the way forward for other projects if we hope to see science-based decision making in government.